I-Flow2

The final design presentation serves as an example of video prototyping and explains a way to experiment with usability testing.

Research Domus Academy Interaction Design 2006

The final design presentation serves as an example of video prototyping and explains a way to experiment with usability testing.

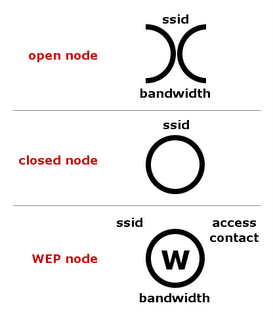

Warchalking is the drawing of symbols in public places to advertise an open Wi-Fi wireless network.

Inspired by hobo symbols, the warchalking marks were conceived by a group of friends in June 2002 and publicised by Matt Jones who designed the set of icons and produced a downloadable document containing them. Within days of Jones publishing a blog entry about warchalking, articles appeared in dozens of publications and stories appeared on several major television news programs around the world.

The word is formed by analogy to wardriving, the practice of driving around an area to detect open Wi-Fi nodes. That term in turn is based on wardialing, the practice of dialing many phone numbers hoping to find a modem. See also demon dialing.

Having found a Wi-Fi node, the warchalker draws a special symbol on a nearby object, such as a wall, the pavement, or a lamp post. Those offering Wi-Fi service might also draw such a symbol to advertise the availability of their Wi-Fi location, whether commercial or personal. The marks are designed to be recognized by those in the know. A well-known photograph of such a warchalk symbol was created by Jones's colleague Ben Hammersley, and has been widely reproduced.

Warchalking never seemed to catch on as an activity, despite its widespread coverage. Instead, the symbols were almost immediately adopted by commercial enterprises interested in or offering Wi-Fi, such as Schlotzsky's Deli's Cool Cloud and JiWire (a Wi-Fi hotspot directory and how-to site). The symbol is now widely used as a shorthand in logos and advertising.

The Warchalking.org domain has been abandoned; it is currently occupied by another party.

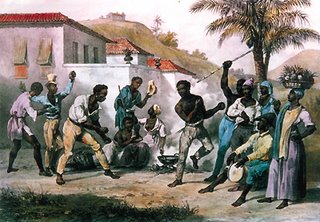

Capoeira (IPA: [kapu'ejɾɐ]) is an Afro-Brazilian martial art developed initially by African slaves in Africa, moving to Brazil, starting in the colonial period. It is marked by deft, tricky movements often played on the ground or completely inverted. It also has a strong acrobatic component in some versions and is always played with music.

There are two main styles of Capoeira that are clearly distinct. Angola is characterized by slower, lower play with particular attention to the rituals and tradition of Capoeira. The other style, Regional (IPA: [heʒiu'naw]), is known for its fluid acrobatic play, where technique and strategy are the key points. Regional was created by Mestre Bimba. Both styles are marked by the use of feints and subterfuge, and use groundwork extensively, as well as sweeps, kicks, and headbutts.

Recently, the art has been popularized by the addition of Capoeira performed in various computer games and movies, and Capoeira music has featured in modern pop music (see Capoeira in popular culture).

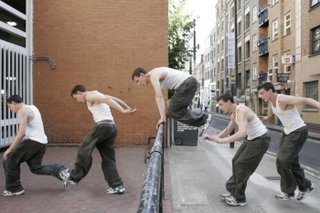

Parkour (IPA: /paʁ.'kuʁ/, often abbreviated PK) is a physical discipline of French origin in which participants attempt to pass obstacles in the fastest and most direct manner possible, using skills such as jumping and climbing, or the more specific parkour moves. The obstacles can be anything in one's environment, so parkour is often practiced in urban areas because of many suitable public structures, such as buildings, rails, and walls.

A traceur (/tʁa.'sœʁ/) is a participant of parkour.

Parkour is an art form of human movement, focusing on uninterrupted, efficient forward motion over, under, around and through obstacles (both man-made and natural) in one's environment. Such movement may come in the form of running, jumping, climbing and other more complex techniques. The goal of parkour is to adapt one's movement to any given obstacle.

According to founder David Belle, the spirit of parkour is guided in part by the notions of "escape" and "reach", that is, the idea of using physical agility and quick thinking to get out of difficult situations, and to be able to go anywhere that one desires. However, fluidity and beauty are also important considerations; for example, Sébastien Foucan, a traceur who trained with Andrew Hahn during the infancy of the art speaks of being "fluid like water," a frequently used metaphor for the smooth passage of barriers through the use of parkour. Similarly, experienced traceur Jerome Ben Aoues explains in the documentary Jump London that:

The most important element is the harmony between you and the obstacle; the movement has to be elegant... If you manage to pass over the fence elegantly—that's beautiful, rather than saying 'I jumped the lot.' What's the point in that?

To some people (particularly non-practitioners), parkour is an extreme sport, to others a discipline more comparable to martial arts. Some consider it a combination of the two, recognising similarities between parkour and the stunts and techniques of Hong Kong martial arts star Jackie Chan, whose fight and chase scenes take place in industrial or urban environments. Still others see it as an art form akin to dance: a way to encapsulate human movement in its most beautiful form. Parkour is often connected with the idea of freedom, in the form of the ability to overcome aspects of one's surroundings that tend to confine; for example, railings, staircases, or walls. The practice of parkour requires considerable physical and mental dedication, and many adherents describe it as a "way of life."

The name parkour derives from the (identically pronounced) French word, "parcours", meaning "course".

The term traceur is the substantive derived from the verb "tracer". Tracer normally means "to trace", "to draw", but it recently (a dozen years) acquired a second, basilectal meaning of "going fast".

Freestyle Parkour (FSPK) or Freerun Parkour (FRPK) is a misnomer sometimes used to describe free running. Use of the term is deprecated among parkour communities, as it implies that the practice is a type of parkour, which is not the case due to the fundamental differences in intention between the two activities.[citation needed]

In the Jump London documentary Sebastien Foucan says, "Free running has always existed, free running has always been there, the thing is that no one gave it a name, we didn't put it in a box." He makes a comparison with prehistoric man, "to hunt, or to chase, or to move around, they had to practice the free run."

Inspiration for parkour came from many sources, one of which is the 'Natural Method of Physical Culture' developed by George Hébert in the early twentieth century. David Belle was introduced to this method by his father, Raymond Belle, a French soldier who practiced it. The word parkour derives from "parcours du combattant", the obstacle courses of Hébert's method and a classic of military training. The younger Belle had participated in activities such as martial arts and gymnastics, and sought to apply his athletic prowess in a manner that would have practical use in life.[1]

After moving to Lisses Belle continued his journey with others.[1] "From then on we developed," says Foucan in Jump London, "And really the whole town was there for us; there for free running. You just have to look, you just have to think, like children." This, as he describes, is "the vision of Parkour."

According to Foucan, the start of the "big jumps" was around the age of fifteen. Over the years as dedicated practitioners improved their skills, their moves continued to grow in magnitude, so that building-to-building jumps and drops of over a storey became common in media portrayals, often leaving people with a slanted view on the nature of parkour. In fact, ground-based movement is much more common than anything involving rooftops.

The journey of parkour from the Parisian suburbs to its current status as a widely practised activity outside of France created splits among the originators. The founders of parkour started out in a group named the Yamakasi, but later separated due to disagreements over what David Belle referred to as "prostitution of the art," the production of a feature film starring the Yamakasi in 2001. Sebastian Foucan, David Belle, and Stephane Vigoroux were amongst those who split at this point. The name 'Yamakasi' is taken from Lingala, a language spoken in the Congo, and means strong spirit, strong body, strong man.

There are fewer predefined movements in parkour than gymnastics and other extreme sports, in that parkour is about unlimited movement over obstacles; the ability to improvise is as important as being able to replicate previously practiced moves.

Despite this, there are many standard "basic" movements that many traceurs practice. Most important are good jumping and landing techniques. The roll, used to limit impact after a drop and to flow easily into the next movement, is often stressed as the most important move to learn.

Vaults are used to clear solid obstacles and come in many forms. Some recognised types of vaults add only technical skill (and hence sometimes aesthetic value) to a move and often not functionality, even sacrificing functionality for a more impressive look. These tend to be looked down on, as they are inefficient movement and thus not truly Parkour. Many vaults are maximally functional to certain situations, but learning specific vaults is not as worthwhile as learning to improvise and adapt to differing situations.

For clearing gaps a number of methods are generally used; each is dependent on the particular obstacle in question, and as with the vaults a good improvisation technique aids traceurs far more than a pre-learned collection of techniques.

Tricks, such as flips, are a topic of much debate amongst traceurs. Most experienced traceurs agree that since flips merely add to the aesthetic value and are rarely (see below) the most efficient way of passing an object, they are not parkour. However, some traceurs believe that tricks add style and total freedom of motion, and that parkour is not so rigidly defined. Free Running, a movement that stems from Parkour, embraces tricks as a way of artistic and physical expression.

David Belle has since released a statement declaring in no uncertain terms that Parkour is about efficient movement, and therefore flips and tricks are (in almost all cases) not Parkour. In this statement Belle also clarified that Free Running and Parkour are two different arts, Free Running being one in which visual flair is also a goal, parkour being solely focused on efficient movement.

A movement by itself is not parkour unless it is used the right way. Vaulting a single rail could be considered parkour so long as it gets you somewhere faster than going around. Additionally, in parkour it should always be possible to return from any place you move to, although not necessarily via the same route.[2]

Pronunciation Key (s

Pronunciation Key (s